After a break for lunch, we set off once again from the junction of the Mumma Farm Lane and Smoketown Road to begin the afternoon portion of the tour, covering the attacks of French and Richardson against the Sunken Road. Vince had several surprises in store here as well.

As he reveals in Unfurl Those Colors, Vince does not accept the standard story of French’s Division blundering blindly into combat at the Bloody Lane. Once again, the terrain provides an important clue. During his initial reconnaissance, Sumner would have seen not only Green’s Division in the swale northeast of the Dunker Church, but also the rebel position in the Sunken Road in the area of French’s attack. In a post-war letter, Sumner’s son, who served as an aide during the battle, explained that he delivered an order to French to press his attack shortly after the advance into the West Woods.

It is important to note French was ordered to “press,” and not to begin, his attack. Also, he describes riding past the position of the Rhode Island Battery on hi way to French. This is a clear reference to Tompkins battery, represented today by the four Parrot Rifles just east of the Visitors Center. Vince argues that the language of the younger Sumner’s recollections suggests not only that French had positive orders to attack where he did so, but also that Sumner was aware of his location from the beginning. There is no similar evidence for Richardson’s Division, though his troops were deliberately held back from Sumner for reasons known only to McClellan.

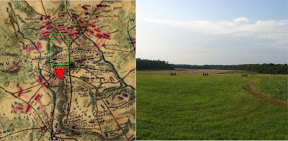

Vince continued on to the Roulette Farm, then northeast along the Roulette Farm Lane to the ravine where the Irish Brigade deployed prior to their advance toward Bloody Lane. The lane itself is hidden from view along the path of their advance until the last 50-100 yards, and some primary source evidence suggests the Confederates may have defended the position from the military crest of the ridge north of the lane for the larger part of the engagement, only becoming trapped in the lane during the final moments of the struggle for Lee’s center.

We moved south toward the lane along the path of the 29th Massachusetts Infantry, the only non-Irish regiment in the Irish Brigade, and also the only unit in the brigade armed with rifles. Their advance also aligned directly with the portion of the Sunken Road obscured by higher ground to the north. These factors combined such that the 29th suffered the lowest loss of the brigade that day. Then too, the 29th did not receive the order to charge in conjunction with the three Irish regiments of the brigade. Vince believes Brigadier General Thomas Meagher, commanding the brigade that day, intentionally left the 29th in position. Meagher states that he decided to trust the impetuosity and élan of the “Irish” in the charge. Perhaps, as Vince suggests, we should take him at his word, and not assume the order to the 29th Massachusetts miscarried.

Though the attack of the Irish Brigade did not gain the position on its own, the situation for the Confederates deteriorated rapidly as Caldwell’s Brigade moved up on the left and flanked their position in the lane. One final item of note concerns the conventional wisdom that the rebel formations defending this area disintegrated and that Lee’s army was finished if only McClellan had followed up this success in the center. But this ignores the presence of Anderson’s Division. Though engaged heavily in the fighting for the Bloody Lane, Anderson’s troops still packed enough of a punch to repulse the advance of the 7th Maine Regiment later that afternoon with heavy loss. The absence of battle reports from Anderson’s Division in the Official Records is lamentable in this case, but Vince is now working on the story of this fight from the Confederate perspective. I look forward to the results of his latest research. If Unfurl Those Colors is any indication, his conclusions will demand we approach the engagement with a fresh perspective, and may shatter long held misconceptions.

4 hours ago