The battle of Bentonville, perhaps the Confederacy’s last hope to stave off final defeat, witnessed the last charge of the Army of Tennessee and was the climactic contest of Sherman’s campaign to subdue the Carolinas. The battlefield is marked by alternating areas of open fields, stands of tall oaks or scrub pine, and swampland. The only elevation changes of note are two depressions. The first of these, formed by a Y-shaped ravine on the western part of the field, figured prominently in the early stages of the fight. The second, formed by the course of Sam Howell Branch, marked part of Johnston’s defensive line on the second and third day of battle.

The action at Averasboro on March 16, 1865, separated the wings of Sherman’s army under Slocum and Howard as Johnston gathered a scratch force combining elements of the Army of Tennessee with forces of the department of North Carolina under Bragg, and of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida under Hardee. The Federal Fourteenth Corps, under Jefferson C. Davis, led Slocum’s advance toward Bentonville along the Goldsboro Road (SR1008).

Bentonville Battlefield is a North Carolina State Historic Site featuring a four stop driving tour. The visitor’s center offers a fiber optic map detailing the events of the first day’s battle, a short introductory film, and a small book store. Contact them for Moore’s Historical Guide to the Battle of Bentonville and Bradley’s Last Stand in the Carolinas. Both of these excellent works are generally unavailable elsewhere. The maps on the battlefield’s web site (http://www.nchistoricsites.org/bentonvi/) are drawn from Moore’s work, one of the finest battlefield guides I have seen. It includes detailed maps for every phase of the action and references to help you orient your view from the various roadside markers on the battlefield, as well as maps for the preceding engagements at Averasboro and Monroe’s Crossroads.

The driving tour at Bentonville contains four stops. Three focus on the action of March 19, while the fourth is near the site of Union General Joseph Mower’s breakthrough on March 21, near the site of Johnston’s headquarters. Numerous historical markers also line the roads that traverse the battlefield. Moore keys all of the maps in his guide (and on the battlefield web site) to the location of these markers, so it is possible to orient the maps from each of them to enhance your understanding of the action. I focused on the main tour stops on this visit.

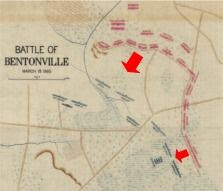

The first stop, “Confederate High Tide,” is just to the north of the Federal line on March 19, where Stewart’s Army of Tennessee drove hard against the Federal center (photo 1). The broad expanse of open farmland framed by woods to the east and west here offered an excellent field of fire for a concentration of Union guns to the south. These cannon shored up the Federal line and unleashed a storm of fire on the charging rebels, buying time for brigades of the Fourteenth and Twentieth Corps to form an effective defense.

While the Army of Tennessee attacked in the center, Hoke’s Division of Bragg’s Department of North Carolina command attacked the Union right defended by Morgan’s Division of the Fourteenth Corps. Stop 2, “Morgan’s Stand,” offers views of the swampy woodland defended by Morgan’s troops (photo 2). Several brigades veered eastward from the Confederate center, increasing the pressure on Morgan and bending his left back perpendicular to his main line. Just as his men repulsed Hoke’s attacks from the west, the rebels appeared in his rear. Morgan’s men, with the pluck of seasoned veterans, simply hopped over their works, fought them in reverse, and repulsed these attacks as well.

Stop 3 of the tour straddles the position of the 100 young soldiers of the North Carolina Junior Reserves, the largest brigade in Johnston’s army. The Reserves were only lightly engaged during the fighting at Bentonville, but their position marks the pivot point between the two Confederate wings in their attacks on March 19. Later, when Howard’s wing of Sherman’s army approached from the east, the Reserves pulled back to the north, forming the southern apex of Johnston’s horseshoe shaped defensive line on March 20-21. The view to the east from this position (photo 3) takes in Cole’s Plantation, where Stewart’s Army of Tennessee attacked and routed Carlin’s Division of the Fourteenth Corps in the opening phases of the battle. The ravine marking Carlin’s position conforms roughly to the tree line visible in the distance to the right.

As the fighting drew to a close on March 19, the hard pressed soldiers of the Federal Fourteenth and Twentieth Corps worked to improve their positions for the expected renewal of the rebel assaults the following day. Johnston, however, taking stock of his losses and the approach of Howard’s wing of Sherman’s army, decided to pull the Army of Tennessee back to his start line. He also ordered Hoke’s Division to disengage and take up a new position fronting eastward across the wooded ravine marking the course of Sam Howell Branch and then bending back to the northwest along the Bentonville Road. McLaws Division deployed to the left of Hoke, and Wade Hampton’s cavalry troopers covered the extreme flank to the north.

March 20 saw no action as Howard’s men moved onto the field and linked up with Slocum’s battered wing. March 21 dawned overcast and rainy, and the armies faced one another over the ramparts of hasty fortifications. Toward late afternoon, Union General Joseph Mower advanced his division without orders and punched a hole in Johnston’s left. Mower’s men surged across large areas of swampy ground and quickly overwhelmed the rebel defenders, nearly overrunning Johnston’s headquarters (photo 4). Johnston and his staff, surprised at this turn of events, fled the area on foot as Generals Hardee and Hampton scraped together available infantry and cavalry for a counterattack. With no support at hand, Mower’s troops grudgingly gave ground and retreated back to their original positions. Howard pressed Sherman for authorization for a general attack, but Sherman demurred.

Johnston’s army withdrew from the field on the night of March 21. This last desperate attempt to stop Sherman’s advance cost his armies 1,527 casualties. Sherman’s forces suffered 2,606 casualties. In less than two weeks, Grant’s armies broke through at Petersburg and began the final pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Johnston withdrew westward toward Durham, North Carolina. He surrendered his army and all Confederate forces east of the Mississippi on April 26, 1865 at Bennett Place, near Durham.

2 comments:

Great post. I have always wanted to see Bentonville.

I've been driving by the site for years traveling up and down I-95. I am glad I finally had a chance to visit.

If you get the chance to do so, be sure to pickup Mark Moore's Guide - it's simply the best battlefield guide I have ever read.

Post a Comment